The Seventies Again: Running with Scissors Meets The Ice Storm

More reflections from the Feral Generation in the Deep South.

Disclaimer: Sorry Mom. I’m outing you just a wee bit, but remember, we’re never fully defined by our not so fine moments.

I’m obsessed with the seventies, the decade in which I came of age. I was born in 1965, so I’m on the mature side of Generation X. If you know me well, you’ve heard me say my childhood was Augusten Burrough’s Running with Scissors meets Rick Moody’s The Ice Storm.

This photo, taken in the basement of my best friend’s house, whose older brother was also my brother’s best friend, sums up the times. You wonder why we became helicopter parents. A lot went on in that basement, which always had a sticky floor and smelled of stale smoke and spilled beer. When Hugo and I became parents during some of our own family’s not-so-wonderful moments, he would say to one of our kids, “Don’t try to pull that crap on me because I’ve seen it all.” Then he’d mutter, “Hell, I invented most of it.”

In the above-referenced basement there was the grow room that said older brothers rigged up. When my brother and his friend decided to go hiking one summer, they left me to take care of the pot plants they babied with an elaborate set up of grow lights they figured out from reading High Times. They had moved them down to our house before they left, but my middle brother—he became an attorney and he was the Maralyn in our Munster family—had protested that under no uncertain terms could they stay at the house.

The day my mother and I moved the pot plants back to my brother’s friend’s house, she crept down Montevallo Road in our orange Dodge Colt covered in bumper stickers—her favorite bumper sticker, God Is Coming and Is She Pissed, was reserved for the brown refrigerator in the kitchen.

I twisted around the front seat to keep an eye on the large green plants waving their star-shaped leaves out the wide-open hatchback just in time to catch the blue and white Mountain Brook police car behind us. My mother caught them in the rearview mirror and shifted gears to turn quickly onto the side street. The plants leaned precariously in the back.

“What are you doing,” I asked, my heart thumping as she drove down the side street.

“We’re waiting here for a minute,” she said and parked in front of someone’s house at the end of the cul-de- sac. She turned off the car, leaned back, and sighed, a fleck of her Revlon red lipstick, the only make-up she wore, on her front tooth. My mother’s short brown hair reminded me of Helen Reddy, whose song “I Am Woman” was her irreverent anthem. I swallowed hard, my throat constricted, and looked around the perfectly manicured lawns to see if anyone had noticed us.

Then she sat straight up, turned the ignition, and we inched back up the hill. At the top, I looked both ways. “Clear,” I said.

She whipped the small square car crammed with pot plants into oncoming traffic, zipped it down the road, and turned too fast into the driveway, scraping the front bumper. We unloaded those plants as fast as we could, glancing at the road, hoping not to see the police cruising by slowly in search of the mother and child with pot plants waving in the wind from the back of their car.

Like a good little sister, I watered those plants diligently. I even added some of my mother’s fertilizer for good measure and stuck the wand attached to the green meter she used to measure the soil’s moisture into each plant before I watered. It never occurred to me, at the time, that this former debutante, tennis playing Junior league mother housing a small pot farm for her son and his friend was out of the ordinary. My mother and I never shopped together, she barely came to any of my track meets, but we bonded as partners in crime to make sure my brother’s pot plants didn’t die while he and his best friend went hiking.

Our “running with scissors” experience can be seen in microcosm at the annual Fourth of July party in our back yard, affectionately known as the “McCullough Creek Country Club.”

At the annual Fourth of July party, no one seemed to care about the overgrown yard, peeling paint, and the fact everything was in disrepair at our ramshackle farmhouse. We had moved there after my grandparents died, and what was pastures and woodlands when my mother was growing up was now suburbia. By the late seventies, my father had left home, and his drinking had left a trail of destruction as only alcoholism can do. My mother was doing her best to finish raising and educating three teenage boys and me as she experienced her own transformation. She was one among the many women sifting through the wreckage of divorce, affairs, and middle-age disappointments. They reinvented themselves right before my adolescent eyes as they became priests, lesbians, crisis center directors, Buddhists, activists, anything but the housewives they’d been groomed to be. Many of these women in my mother’s neighborhood friend group had pitched in to create “The McCullough Creek Country Club,” where they helped my mother pay the pool expenses. They and their kids often came and went to swim in the long rectangular pool, originally dug by a man and a mule during the 1930s, that we eventually painted black.

That Fourth of July the picnic table was full of slabs of ribs, potato salad, pea salad, baked beans, Mrs. M’s famous meringues and a whole mess of everyone’s special dishes they brought along with red Igloo coolers of beer and wine. My mother stood a good portion of the picnic manning the huge rusting black barrel of a barbecue pit, turning ribs with her tongs in one hand, her drink in another, wearing a straw cowboy hat and her one-piece bathing suit. She wielded her tongs around as she talked to a friend, who sat in a butterfly chair nearby and tapped her ashes into the steel hubcap someone found and turned into an ashtray, her legs propped up on the industrial wooden spool now serving as a table.

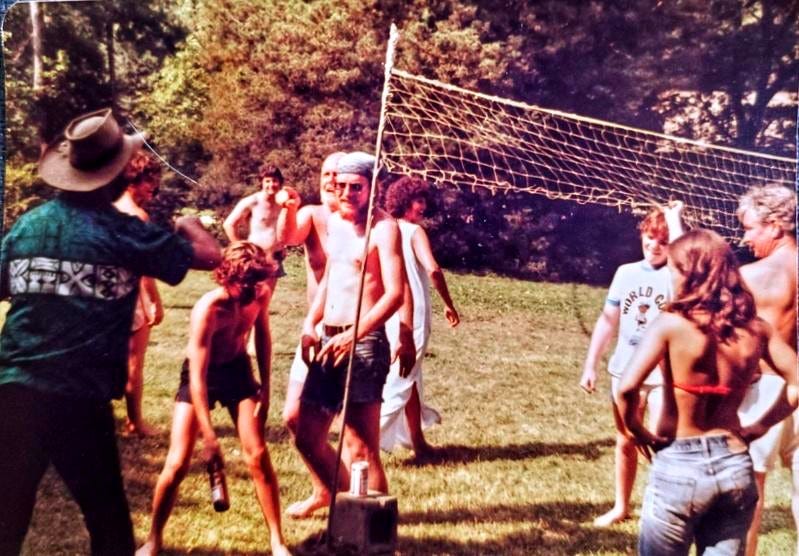

Adults and teenagers in various stages of dress streamed from the pool area to the picnic table to the volleyball or badminton court, where a game between adults and teenagers was in progress. Carl, the flamboyant director of the local theater, but on July the 4th the self-appointed umpire, was arguing loudly, hands on his hips and his hairy chest spilling out of his partially buttoned colorful shirt.

The older teenage boys always protested his calls since he called in favor of the adults every time there was a dispute. By the end of the volleyball game, Carl’s long list of miscalls ultimately resulted in a throng of boys throwing him into the pool, which was his end game all along. A few other fully dressed adults, well into their red silo cups, joined him. A frenzy of “Oh shit, I forgot this was in my pocket” ensued as drunk parents and friends threw packs of cigarettes and wallets onto the concrete decking. Adults and teenagers drifted in and out of the house and by the pool until late at night, and the next day there were always mishaps to tell, mysteries to solve and pieces of stranded clothing to reconnect with the hungover owner.

How we excelled in school and were admitted to elite colleges I’ll never know. When I revisit the past with my mother, the zanier times, the challenges she faced entering the workforce for the first time in middle age, the benign neglect and the real damage done, she always shrugs it off by saying it made us stronger. Raised without restraint in the seventies and feeling the wide-open nature of society after the hard-won gains of the civil rights movement and Roe v. Wade, we are a resilient, resourceful generation who once listened to 8 track cassettes and went to concerts for pennies without worrying about a mass shooting to now having pivoted and adapted at every imaginable downturn and technological advancement to converse with AI. We were spoon fed on chaos and change and that’s why we are best suited, in many ways, to resist the current catastrophes engulfing us at this pivotal moment.

It’s a strange journey as one of the Feral Generation, but I wouldn’t have it any other way.

The party faded as kids scattered to college, the adults sort of straightened up, Carter left office, and the era of big hair, greed, AIDS and Jerry Falwell came crashing in. That’s not to say the eighties weren’t their own special brand of craziness that was equally confounding, but that’s for another Substack, so as brother Billy always says, “Stay tuned for further episodes.”

A Few Books I Love Featuring the Seventies:

I just finished Adam Ross’s Playworld about a kid actor growing up in New York during this time. The NYT reviews is titled “The Hero of This Novel is 14. His Married Girlfriend is 36.”

Kids in America by Liz Prato is a fabulous collection of essays. You have to love this description: Liz Prato reveals a generation deeply affected by terrorism, racial inequality, rape culture, and mental illness in an era when none of these issues were openly discussed. That about sums it all up right there.

Why We Can’t Sleep looks at Gen X women’s midlife crisis and what fuels it by Ada Calhoun

The Ice Storm by Rick Moody was published in 1994 and set in 1973 when a freak snowstorm envelopes an affluent Connecticut suburb.

Running with Scissors Augusten Burrough’s memoir about coming of age in the 1970s.

A recent article comparing Gen X to candlestick makers in the age of electricity.

Great response to this article:

Gen X Strikes Back by Jonathan Small

I know you meant to say, “Sorry Reb — and Sherwood, Bill, Bruce,” et al. 😎

"We were spoon fed on chaos and change and that’s why we are best suited, in many ways, to resist the current catastrophes ..." Amen to that! Loved reading such a colorful account of your upbringing.